Beyond the Triple Hurdle: How to Finally Make Interregional Transmission Work in the Northeast.

Drawing from 15 years of experience at MISO, I share suggestions to help the Northeast States Collaborative turn its interregional transmission plan into real steel in the ground.

Executive Summary

The Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission has taken an important first step by releasing a Strategic Action Plan that identifies the “missing middle” in how we plan, evaluate, and advance interregional transmission across PJM, NYISO, and ISO-NE. The plan rightly highlights the gaps in current planning processes, the triple hurdle of approval, and the lack of alignment in benefits and cost allocation.

But if this Collaborative wants to move from coordination to actual projects, RTO alignment alone won’t cut it. States like New York and Massachusetts—both out front on climate targets—need to step up and start driving the conversation. That means asking for more than generic commitments. It means pushing for regulatory clarity, better data, and modeling that reflects real-world constraints and public policy priorities.

New York’s CLCPA and Massachusetts’ offshore wind and storage mandates aren’t just ambitious—they’re unworkable without serious interregional buildout. That means cutting through queue silos, fixing how benefits and costs are assigned, and making sure state-led planning efforts don’t get sidelined by opaque RTO processes in PJM, NYISO, or ISO-NE.

Drawing on my 15 years of experience at MISO, I offer seven suggestions to strengthen the Collaborative’s efforts—from recognizing that this is fundamentally an economic—not a reliability—problem, to improving how production cost models are run, harmonizing queue assumptions, and ensuring RTO staff have a formal role in this work. If the Collaborative is serious about moving projects forward, it needs to go beyond high-level coordination and start making modeling and regulatory decisions that will stand up in an RTO process.

Background

The Northeast States Collaborative on Interregional Transmission (“Collaborative”) comprises all the Mid-Atlantic states in PJM, as well as New York, and all the New England states in ISO-NE. These states have recently released a Strategic Action Plan (“Plan”) outlining near-term and short-term steps to catalyze interregional transmission.

The problem that this Collaborative has identified is a real one: interregional transmission. The identification of transmission needs among regions as large as PJM, NYISO, and ISO-NE is a challenging problem to solve because each of these ISOs is engaged in its regional planning efforts. Layering an interregional transmission planning effort on top of their current FERC-approved tariff may seem like extra work unless someone, such as the Collaborative, develops a list of interregional projects.

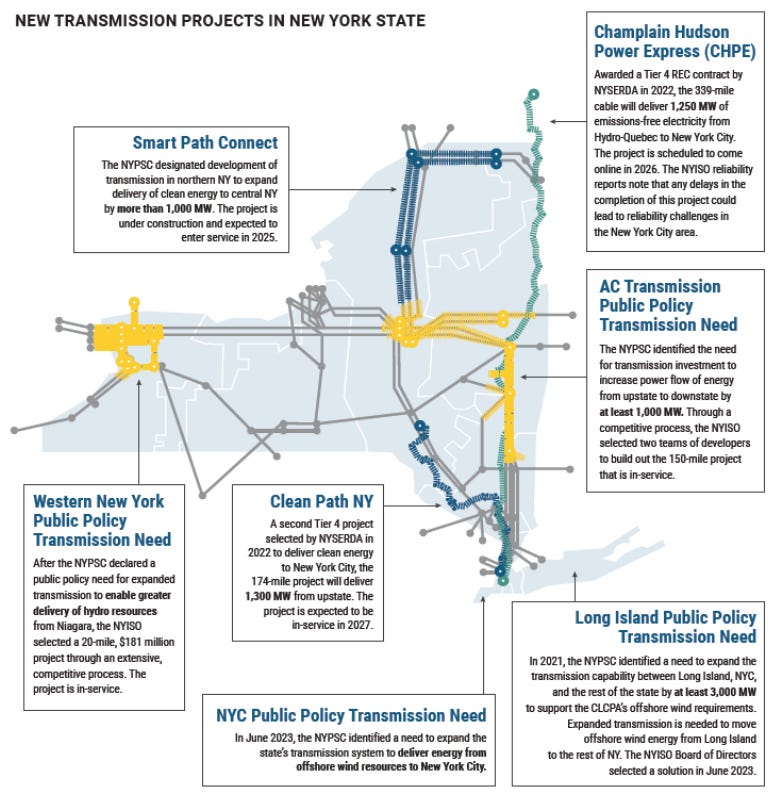

Source: NYISO

To my knowledge, no state has attempted to proactively bring a transmission project to a Regional Transmission Organization for inclusion in its Transmission Expansion Plan. Typically, state commissioners participate along with their regulatory staff in the RTO’s transmission planning stakeholder process in a partially engaged manner. By that, I mean, state commissioners do not want to “approve” a transmission line by voting for the RTO’s transmission expansion plan because they want to preserve the right to decide on the line when it comes before them in a Certificate of Public Convenience & Necessity (CPCN) proceeding.

Hence, state Commissioners know which line is approved by the RTO Board and wait for the transmission owner in their state or an independent transmission developer to bring it forward in a CPCN proceeding for approval. I would assume that any interregional transmission identified by the Collaborative needs to undergo a similar process. I am unsure if the states involved in the Collaborative have considered these regulatory steps yet.

Triple Hurdle and the Missing Middle

The Plan prepared by Brattle mentions this “triple hurdle” problem of interregional transmission. The first and second hurdles are in the two regions where interregional transmission is contemplated. The third hurdle is bringing this together and evaluating the interregional transmission to determine the benefits to the two regions. In other words, interregional transmission should not only benefit both PJM and NYISO combined but also benefit individual PJM and NYISO customers. It is akin to treating PJM and NYISO as a single pool or a single market.

The Plan stated that interregional transmission is not considered currently because of “the timing misalignment of regional planning cycles across regions, divergent benefit calculations, and absence of a clear interregional needs identification process, potentially beneficial interregional projects are not identified or meaningfully considered in the ongoing development of regional plans”.

The Plan states that the Collaborative understands that no process currently exists “groups of states spanning different transmission planning regions to take the various steps necessary to identify, evaluate, select, and agree to share the cost of beneficial interregional transmission projects so they can be developed”. Members of the Collaborative refer to this gap as the “missing middle” problem. Identifying beneficial interregional transmission projects and making them actionable within the existing regional planning process is the missing middle issue.

To address this missing middle issue, the Plan recommends two steps for the Collaborative: 1) identification of interregional transmission projects and proposing them to PJM, NYISO and ISO-NE, 2) develop a cost allocation for these interregional projects.

Low-Regrets Transmission Expansion Estimates.

The Plan has estimated the amount of interregional transmission that needs to be built under both scenarios, without decarbonization targets and with decarbonization targets.

Without the need to meet decarbonization targets, the Plan estimates 2 GWs of “low-regrets” interregional transmission expansion needs between PJM and New York, and 1.7 GWs between New York and New England by 2035. By 2040, these needs are expected to grow to 4 GW between PJM and New York, and 3 GW between New York and New England.

Assuming the need is met to fulfill decarbonization targets by 2040, the Plan estimates 4.5-6 GW between PJM and New York and 4-7 GW between New York and New England.

Seven Suggestions for the Collaborative

In addition to the Plan, I offer the following unsolicited suggestions for the Collaborative, based on my 15 years of transmission planning experience at the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), during which I regularly interacted with both SPP and PJM transmission planning staff and states within these three Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs).

1. The Collaborative must agree that this is an economic analysis problem, not a reliability problem.

The first suggestion for state regulators and agencies involved in the Collaborative is to realize that they are dealing with an economic problem, not a reliability problem. They are doing this for economic benefits, not reliability benefits. There is no “if we don’t do this, the lights won’t stay online” problem here; hence, it is not a reliability issue. As I understand the Collaborative’s objective, it's more about “we are doing this so that consumers in our states realize the benefit of interregional transmission” – that’s an economic issue.

The reason this economic versus reliability issue is important is that the Collaborative needs to run a production cost model (e.g., PROMOD) first, rather than a reliability model (e.g., PSS®E). That makes all the difference because first they need to understand where the power wants to flow under the with/without decarbonization targets scenarios. If it were MISO, the power would want to flow from wind-rich areas in Minnesota and Iowa to Chicago, which is in PJM. The models should allow power to flow without existing transmission constraints.

2. The Collaborative must conduct a copper sheet analysis to determine where the power wants to flow.

Allowing the production cost models to simulate where the power wants to flow means removing the existing transmission constraints. The Collaborative needs to remove the existing transmission constraints between PJM and New York, as well as between New York and New England, from the production cost models. The PJM-New York-New England must operate as a single power market in the production cost model. Otherwise, the model will always prefer PJM generators to meet the PJM load first, and only if there is excess PJM generation will it consider its neighbors for pool-to-pool transactions.

The production cost models currently show PJM as a single pool, New York ISO as a single pool, and the same as ISO-NE. Without combining PJM, NYISO and ISO-NE as a single market, the model will always prefer individual generators to first meet the native load in those markets. And any excess generation will be a sale to its neighboring region based on the “hurdle rate”.

If there are no transmission constraints or regulatory barriers to power exchanges between existing markets, then the model has a $0/MWh hurdle rate.

Source: MISO

However, if there are barriers to power purchases between PJM and NYISO, then the model has a higher hurdle rate, such as $10/MWh. This means that the model would initiate transactions between PJM and MISO first to export excess PJM generation due to the lower hurdle rate, rather than looking east towards NYISO because of the higher hurdle rate. Combining all three regions into a single power pool in PROMOD addresses this issue.

Then the next issue for the Collaborative is to decide who they want to trade with first if there is excess generation in their Collaborative power pool. Likewise, if they are deficient, who do they want to depend on? This is a relevant question because this PJM-NYISO-ISONE is not an island. The combined Collaborative region would still have transmission ties to MISO, Southeast, Florida and Canada.

3. The Collaborative needs to agree on how future generators in the interconnection queue will be treated.

The Collaborative is focused on identifying transmission needs for integrating Off Shore Wind (OSW) to meet the decarbonization targets of individual States in the combined Mid-Atlantic and New England region. The Collaborative recognizes that both onshore and OSW need to be considered initially to identify the interregional transition projects.[1]

However, the Collaborative also needs to recognize and reach an agreement on how to model the existing proposed generators in each RTO generator queue. This agreement is relevant because it is well understood that not all generators in the interconnection queue will have a signed Generator Interconnection Agreement (GIA), only 25% of the proposed projects will have a signed GIA.

Is the Collaborative seeking to identify interregional transmission for all generators seeking interconnection? If so, what is the cut-off date? For example, will generator projects submitted in PJM’s latest queue cycle be considered? Or would the Collaborative consider only PJM-queued projects submitted before 2025? Similar questions need to be asked and answered for the NYISO and ISO-NE regions. These are relevant because the answers to these questions determine the extent to which the interregional transmission needs to be planned.

Source: PJM

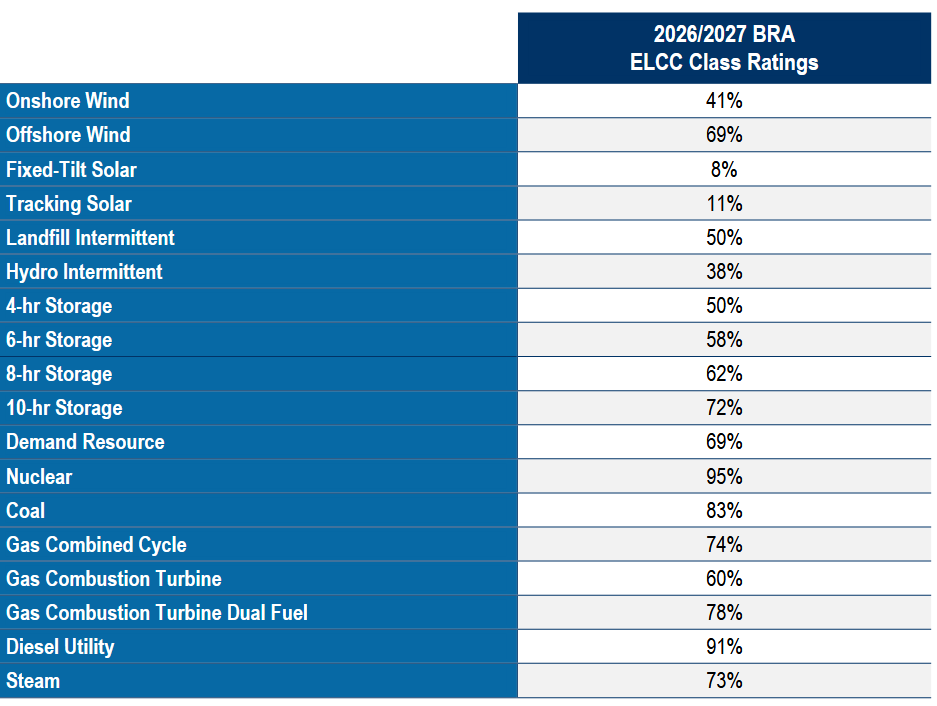

The Collaborative also needs to harmonize the study assumptions for both existing generators and future generators among the three regions. For example, the Collaborative needs to understand how the three regions differ in terms of capacity credit for renewable generators, how these generators are dispatched, when energy storage is dispatched, and what percentage of their rated capacity is utilized.

For example, see PJM’s and NYISO’s capacity accreditation values below: (notice, a 4-Hour battery is given a capacity accreditation value of 78.53% in New York City for 2025-2026 capacity auction, but, at PJM, that same 4-Hour battery is given 50% capacity value. Those differences is what I mention above.)

Source: NYISO

Source: PJM

The dispatch assumptions are relevant because they determine the need for transmission. If the power wants to flow along a certain transmission path, it will appear in these production cost models as having a high shadow price ($/MW/hr). That high price indicates transmission congestion, meaning there are low-priced generators available but cannot get across due to limited transmission capacity. That is how candidates for interregional transmission are identified – by identifying areas where congestion occurs in this combined three-region pool.

How many hours during a year are the existing transmission facilities “binding”? That question determines where transmission needs to be beefed up. That is also why this is a production cost model issue, not a reliability model issue, because the reliability model is only a snapshot in time for a specific case, such as a summer peak. If an existing transmission facility or a bunch of facilities called “flowgate” are binding for 75% of the time in the study year, that shows a clear need for interregional transmission.

4. The Collaborative needs to agree on a limited number of scenarios to run.

It is also worth mentioning that the Collaborative needs to set its sights lower initially. One way to do that is to limit the number of study scenarios. Having too many scenarios will bog down the Collaborative.

The Collaborative may be tempted to run scenarios on high natural gas prices, aggressive goals for OSW, nuclear plant additions or retirements, high load growth, and high decarbonization targets. Each of these scenarios will appear logical to identify interregional transmission needs. In an ideal world with infinite amount of time and modeling, these are worthwhile to run. But if the Collaborative is after a “low-regrets” plan, running multiple scenarios will consume too much time and effort.

That is why the Collaborative needs to agree on a common set of scenarios or, at most, two scenarios. This keeps the scope of the Plan tight. As the Collaborative realizes, the RTOs still need to run the identified interregional projects through their planning processes.

5. The Collaborative needs to run the reliability analysis after interregional transmission is identified.

To truly identify the “low-regrets” plan, the Collaborative needs to run the reliability analysis on projects identified from the production cost analysis. This step shows the reliability benefit of the proposed economic projects. This step will determine whether the proposed economic projects meet the NERC transmission planning criteria. Any proposed transmission must also meet the NERC planning criteria, as RTOs serve as both the Planning Authority for their regions and the Balancing Authority. This means they must propose a transmission that meets NERC’s planning criteria.

6. The Collaborative must formalize the role of Grid Operators.

The Collaborative rightly notes that there are staffing limitations at these RTOs. The Plan suggests that the Collaborative engage RTOs/ISOs as technical advisers. There is a risk to this approach. Without a formal FERC tariff-justified role for the RTO staff, I am concerned that these technical advisers will naturally lose interest and stop participating in the Collaborative’s efforts when it matters most, as they will always prioritize what their tariff dictates.

Demanding the time of existing transmission planning staff at these RTOs means showing a clear line of sight to which line item in the transmission Tariff they are working on. Without that linkage, the planning staff will treat this like a networking event.

A formal FERC tariff-defined role for these technical advisers will serve to inform transmission owners at these RTOs as well. These transmission owners are paying the salaries of RTO employees, to put it bluntly. The last thing the Collaborative wants is to steal staff time working on regional transmission at these RTOs. That jeopardizes the transmission owners. Obtaining FERC’s approval through a tariff that formalizes the role of RTO staff in identifying interregional transmission will save the Collaborative a lot of time and headaches later. It does not have to be a Tariff; it could be a Policy Statement from FERC.

7. The Collaborative needs to define how it wants to interact with EIPC and EISPC.

The Plan discusses the role of the IPSAC - Interregional Planning Stakeholder Advisory Committee for PJM/NY/NE and Joint ISO/RTO Planning Council (JIPC). The Collaborative would make a formal request to the JIPC to evaluate interregional projects. While this indicates that some thoughts are behind collaboration with existing stakeholder frameworks, there is no mention of the Eastern Interconnection Planning Collaborative (EIPC) or the Eastern Interconnection States Planning Council (EISPC). Depending on where EIPC and EISPC are today, it might be worthwhile for the Collaborative to establish formal arrangements with these two organizations so that it does not cross wires with them later.

Conclusion

The Strategic Action Plan is a fine first step. But unless states like New York and Massachusetts step up and start asking harder questions—about modeling assumptions, benefit alignment, and actual project selection—this will go the way of every other well-meaning coordination effort: nowhere fast.

New York can’t hit its CLCPA targets, and Massachusetts won’t get its offshore wind to shore, without interregional projects that make it through the gauntlet of RTO processes. If you work in a state agency, an ISO stakeholder group, or a governor’s energy office, now’s the time to speak up. Because this isn’t a reliability problem anymore—it’s an economic and regulatory bottleneck. And if the states don’t take ownership of it, no one else will.

[1] “The RFI would encourage the (if needed, confidential) submission of project ideas on either the PJM-NYISO or NYISO-ISO-NE interregional seam, allowing for both offshore and onshore transmission solutions as well as solutions that are synergistic with the regions’ need to create the grid capacity necessary to integrate clean-energy resources, such as offshore wind generation.” Page 4, Report.

Here is a link to the RFI that was issued recently -https://energyinstitute.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Northeast-States-Collaborative_RFI_FINAL-6_20_25.pdf