Bring Your Own Generation: PJM’s Most Controversial Idea Yet.

A quick summary of stakeholder comments with and without attribution.

Introduction: Why BYOG Matters

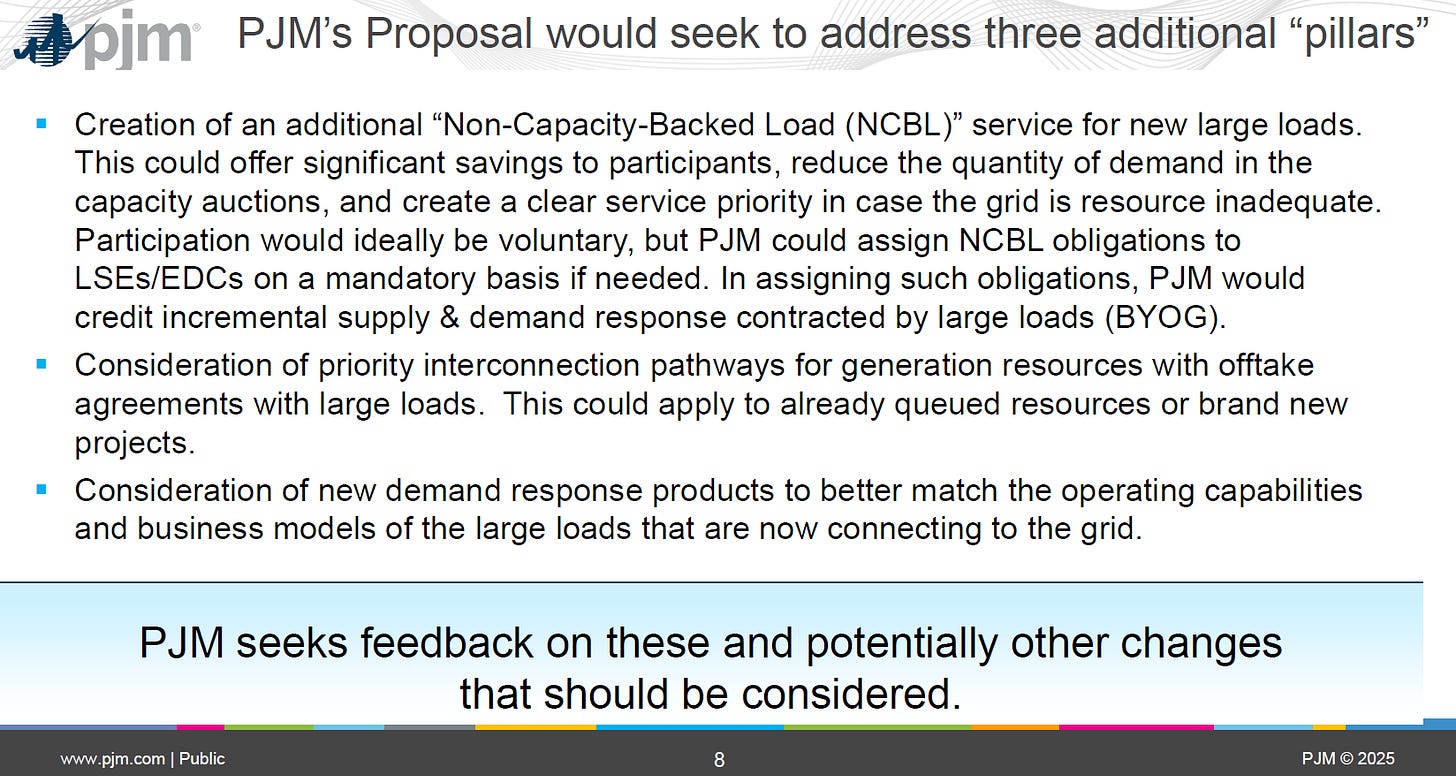

PJM’s Large Load Additions process is about how to handle explosive data center growth. Its conceptual proposal rests on a new category called Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL), under which large new loads can avoid capacity obligations if they bring their own supply or flexibility.

Source: PJM

One key option is “Bring Your Own Generation” (BYOG) — allowing large loads to match demand with new generation or demand response. The stakes are big: resource adequacy, interconnection delays, consumer costs, and fairness across stakeholders. The debate isn’t whether BYOG should exist, but how it should be designed — voluntary, mandatory, or somewhere in between.

Source: PJM

Section 1: The Only Way Forward?

AEU put it bluntly: “The only way for new large load to come to PJM in the near term.” Many stakeholders echoed that BYOG could be a practical pathway for large loads to interconnect more quickly, and Org 1 called the idea “constructive, nondiscriminatory, and consistent with PJM principles and federal policy.” Still, BYOG wasn’t PJM’s standalone proposal — it was framed as a credit within the Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) concept.

Supporters see it as pragmatic, but caveats remain: air permit limits on diesel run time, questions about fairness, and legal concerns if BYOG or NCBL were made mandatory. Others, like Org 9, warned that BYOG could look like queue-jumping if it gives new loads preferential interconnection treatment.

Section 2: Affordability First

NJ Rate Counsel captured the point clearly: “An unaffordable solution is nothing more than an academic exercise.” Affordability is always top of mind for states, and PJM states are rightfully concerned about how wholesale market outcomes filter down into consumer bills. PJM’s own presentation showed that large loads opting for Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) could avoid significant capacity costs, and BYOG was framed as one way to reduce that NCBL obligation.

That is the opportunity in front of PJM: to show the combination of NCBL and BYOG as a consumer protection tool. If framed that way, PJM earns not only regulatory credibility but also political cover — especially with gubernatorial elections in Maryland and New Jersey this November, where electricity costs are already a campaign issue.

Stakeholders pushed the point further. IL OAG argued that extraordinary large loads should be required to BYOG outright, ensuring the burden is on new customers and not shifted onto existing ones. But others, like Org 1, warned that mandatory BYOG/NCBL would be discriminatory and likely fail at FERC.

Summary: Without BYOG, the costs of large new loads risk being socialized onto existing customers. With BYOG, PJM can credibly argue that new loads carry their fair share — a message that works for both policy and politics.

Section 3: Make BYOG Mandatory?

IL OAG cut to the chase: BYOG should be made explicit in PJM’s framework — and maybe even required. Making BYOG mandatory for new large loads, they argued, avoids ambiguity, ensures fairness, and keeps the burden from falling back on existing customers.

PJM itself, however, framed BYOG differently. In its August 18 proposal, BYOG was presented as an offset within the Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) construct, not as a stand-alone mandate. NCBL would begin as a voluntary option, with the possibility of mandatory assignment only if PJM faced a supply shortfall.

Consumer advocates raised important concerns. PA OCA questioned how BYOG should be defined, how reliable backup generation is, and how to distinguish between front-of-meter and behind-the-meter resources. And Org 1 went further, warning that mandatory BYOG or NCBL “would almost certainly fail under FERC’s nondiscrimination standards”.

Summary: The open question is whether BYOG should remain incentive-driven or evolve into a firm obligation. Stakeholders like IL OAG see it as essential, while others see legal and fairness risks in making it mandatory.

Section 4: From Theory to Practice

The Data Center Coalition (DCC) put it bluntly: BYOG remains “theoretical” without clear rules of the road. That criticism cuts to the heart of PJM’s challenge. Unless PJM provides concrete design details, BYOG risks staying on the whiteboard instead of moving into reality.

Anonymous commenters — Orgs 5, 7, and 8 — echoed the same frustration. They highlighted the lack of clarity around timing, true-ups, and whether BYOG would actually accelerate go-live schedules. Even load-side stakeholders who support BYOG hesitate to commit until PJM defines how participation will work.

PJM’s conceptual proposal framed BYOG as part of the Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) construct, not as a stand-alone product. Some stakeholders worry that without clear rules, BYOG’s potential will be undercut, while others (like Org 8) said NCBL itself could work if it enabled faster interconnection — but would be a “tough pill to swallow” otherwise.

Summary: BYOG’s biggest proponents want PJM to move quickly from concept to practice. Without clear participation pathways, it risks being overshadowed by NCBL rather than becoming the accelerant that large loads are looking for.

Section 5: Proximity Matters

The PJM Industrial Customer Coalition (PJMICC) hit on an important nuance: accelerated BYOG interconnection should only apply if the generation is on-site or geographically proximate to the new load. That condition, echoed by Org 9, would make BYOG more workable and address fairness concerns by limiting cost-shifting and preventing queue bypass.

PJM’s own presentation only floated the broader concept of priority interconnection pathways for generation tied to large loads. Stakeholders like PJMICC narrowed this into a proximity test. The appeal is practical — localized BYOG reduces transmission needs and avoids recreating the same interconnection problems PJM is trying to solve.

But not everyone agrees. Vistra and others warned that limiting BYOG to on-site or local projects could be discriminatory against existing generation already in PJM’s queue.

Summary: Proximity rules make BYOG cleaner and fairer in the eyes of many customers, but PJM will have to balance those benefits against concerns about open access and discrimination.

Section 6: Generation Without Transmission Is Useless

Google raised a sharp concern: even if a new large load brings its own generation, transmission constraints could still block interconnection. In that case, BYOG fails before it even starts. Google’s call is for PJM to take a “more active and assertive role” in transmission-level load interconnection requests.

PJM’s own proposal, however, was clear that Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) — even when paired with BYOG — would still count as network load in planning studies, and upgrades would be identified to serve it reliably. In other words, BYOG doesn’t erase the need for transmission analysis.

It’s a fair point — but I worry this could bog down BYOG before it gets a chance to prove itself. If a large new load brings generation that offsets its demand, then in theory it should have a net-zero effect on transmission constraints. If there’s already a constraint, BYOG shouldn’t make it worse; and if there isn’t one, BYOG shouldn’t create a new one.

That’s why I think PJM’s role here should be analytical, not procedural. PJM could model and publish transparent studies showing that a new large load with BYOG is not worsening transmission constraints. That would go a long way toward addressing Google’s concern without dragging the whole BYOG idea into PJM’s transmission quagmire. Over time, as PJM gains experience with BYOG — and as aggregated DERs come online under FERC Order 2222 — it can return to the deeper transmission bottleneck problem.

Summary: BYOG’s promise could be undermined if transmission isn’t addressed. The challenge for PJM is to show, with transparent analysis, whether new load plus new generation truly balances out — without creating new unfairness in the queue.

Section 7: Details, Details, Details

Google raised the most detailed list of questions about BYOG design, covering everything from eligibility to ELCC volatility. Their point is fair: without answers to these, BYOG can’t scale. But my view is that PJM doesn’t need to overcomplicate the first iteration.

Eligibility & Portfolios: Google asks whether BYOG must be a one-for-one accredited MW match and whether portfolios like solar plus storage could qualify. To me, this should be left to the states. PJM doesn’t need to referee whether batteries count while diesel generators do not. If a new load shows it has sufficient BYOG to cover its obligations, PJM’s job is done. Accreditation can come later, once PJM has experience.

Deliverability & Ramping: Google inquires about timelines and the implications of a delayed BYOG. If PJM follows PJMICC’s proximity principle and limits BYOG to on-site or local generation, these concerns are largely moot. No need for a new queue.

Compliance & Permanence: Google wants to know how PJM will enforce rules and whether BYOG is permanent. I don’t see the problem Google sees. PJM needs to verify that the load is offset by generation so it doesn’t trigger new capacity or transmission obligations. As for permanence, a five-year trial period would be enough for PJM to gain experience before locking in long-term rules.

Accelerated Interconnection: Google asks if BYOG should qualify for expedited studies. The answer should be no. Creating a “BYOG queue” invites direct comparisons to PJM’s FERC-jurisdictional interconnection process — and fairness concerns would drag the whole effort down. If a large load uses a generator already in PJM’s queue, it should need a signed GIA. Otherwise, PJM should treat BYOG like BTM generation: not queued, but verified.

LDA Deliverability: Google worries about mismatches across Locational Deliverability Areas. The answer should be yes — BYOG must be in the same LDA as the load, or at least proximate across an LDA border. Again, this matches the PJMICC principle and keeps rules consistent.

Demonstration Commitments: Google asks if provisional commitments should count. If BYOG is modeled like BTMG, then this question goes away. A BTM-style framework means no queue entry, just a demonstration that the generation is at the site and tied to the load.

ELCC Volatility: Google is concerned that volatile ELCC values could undermine BYOG. One option is for PJM to publish forward-looking ELCC estimates to give participants visibility. But if BYOG is not bidding into the BRA, PJM may not even need to calculate ELCC at all.

Summary: For BYOG to work at scale, PJM must answer these design questions. But the answers don’t all have to come now — PJM can launch a simple, state-aligned BYOG process and refine over time.

Section 8: UCAP for UCAP

MN8 Energy made its position clear: if a new large load uses BYOG, it should bring at least an equivalent amount of UCAP into PJM’s markets. In other words, “UCAP for UCAP.” This is meant to ensure BYOG strengthens, rather than weakens, PJM’s resource adequacy framework.

MN8 also argued BYOG should be technology-agnostic, focused on RA attributes, and designed with safeguards to protect prior-queued projects. They suggested two study-process fixes: running counterfactual interconnection cases to hold prior projects harmless, or conducting concurrent studies so BYOG projects don’t get preferential access to transmission.

I think most of these concerns are less pressing in a first iteration of BYOG. Since PJM isn’t creating a formal BYOG generator queue like the existing GIQ, worries about counterfactual studies and cost allocation may be premature. The real task is to launch a simple BYOG model that works for new loads now, while leaving room for adjustments once PJM has practical experience.

Summary: Without UCAP alignment, BYOG risks weakening PJM’s resource adequacy construct. But in the early stages, PJM should resist overcomplicating the process with UCAP debates better suited for a later phase.

Section 9: Unjustified Taking

Vistra didn’t mince words: excluding existing generation from BYOG contracts would be discriminatory and “likely indefensible at FERC.” That’s a serious charge — and one PJM can’t afford to ignore.

To me, the answer is straightforward. PJM should allow new large loads to bring either new or existing generation into BYOG arrangements. If a new large load chooses to rely on existing resources, the responsibility should fall on the load to prove the impact is net zero. PJM’s role should be limited to verification: ensuring that BYOG does not add to resource adequacy problems or create new transmission constraints.

Vistra’s argument is part of a broader fairness chorus. Org 12, Shell, and SEIA all raised concerns about queue jumping, carve-outs, or special treatment. The common thread is clear: BYOG must not undermine PJM’s open access principles.

Summary: BYOG must avoid creating discriminatory shortcuts that pit new loads against projects already waiting in PJM’s interconnection queue.

Section 10: Will BYOG Move the Needle?

Org 8 put it simply: if BYOG doesn’t accelerate the go-live dates for new large loads, then it’s irrelevant. I agree. The entire point of BYOG is to make interconnection faster and less burdensome. If the timelines don’t change, BYOG risks becoming an empty gesture.

Org 7 added another caution: combining BYOG with Non-Capacity Backed Load (NCBL) “would likely be unsuccessful.” I share that concern. Tackling both concepts at once risks pulling PJM into two uncharted territories at the same time. PJM should take BYOG on its merits first, gain at least five years of practical experience with large loads using BYOG, and only then revisit NCBL.

PJM’s actual proposal, though, moved in the opposite order — advancing NCBL as the central construct, with BYOG and demand response as credits and enhancements layered into it. Some stakeholders supported that sequencing, seeing NCBL as a necessary transitional tool even if BYOG design takes longer.

At bottom, the skeptics are right about one thing: if PJM layers complexity without solving the fundamental timing issue, BYOG won’t move the needle.

Conclusion: Acronym or Answer?

The idea of Bring Your Own Generation has sparked one of the broadest debates I’ve seen in a PJM stakeholder process. Everyone has an opinion. Consumer advocates frame BYOG as a way to prevent cost socialization and protect households from paying for 32 GW of new load. Load interests view BYOG as a means to expedite interconnection and avoid being classified as non-firm. Generators insist it must be fair, nondiscriminatory, and consistent with FERC’s open access rules. Developers argue it must be tied to real RA attributes. And even data centers themselves say they are open to BYOG — if PJM can move it from theory to practice.

What’s striking is that most stakeholders supported BYOG in principle, but only with conditions. The debate has been about how to design it: voluntary or mandatory? On-site only or broader? UCAP-for-UCAP or flexible? Permanent or trial-based? Fairness safeguards or fast-track privileges? Some, like Vistra, warned that excluding existing resources would be indefensible at FERC; others, like MN8, pressed for UCAP alignment.

PJM’s own proposal, however, centered on Non-Capacity-Backed Load (NCBL) as the transitional construct, with BYOG credited as one way to reduce those obligations. The choice now is whether BYOG will be integrated into NCBL in a way that balances flexibility for large loads with PJM’s open access obligations.

My view is that the path forward should be clear. Start small, keep it simple, and avoid creating a new interconnection queue that drags the process into endless FERC litigation. Treat BYOG like behind-the-meter generation: loads must prove net zero impact on resource adequacy and transmission, and PJM’s job is to verify. Begin with a five-year trial window, learn from experience, and adapt as real projects come online.

If done right, BYOG could ease the political pressure on PJM, help states make the affordability case, and give large loads a constructive way to participate in the market. If done wrong, BYOG will just be another acronym on a long list of PJM pilot ideas that promised much and delivered little.

The choice is in PJM’s hands: will BYOG become a real solution — or just another footnote in the alphabet soup of PJM acronyms?

"Proximity Matters" should be the title of this. Each concern could be alleviated if this was the prime focus. Affordability, access, etc. Good for Google, MN8 and Vistra for pushing in the right direction. Rao is right - the process could layer atop the good idea and smother it.